What I Worked On: Small-Time Data Scientist Edition

Tracing the messy path of your intellectual development

In February, the computer scientist Paul Graham posted a long essay called “What I Worked On” to his blog. The piece is a comprehensive account of his professional development, taking readers through his earliest encounters with computers, his work on the programming language Lisp, and the creation of Y Combinator, the pioneering startup accelerator. Interspersed with Graham’s professional milestones are serious forays into decidedly non-programming activities like art school and painting. He ends by declaring his career a “messy” one, because it doesn’t have a straight narrative that threads through every piece neatly—but he hopes such a written account of a successful person’s wanderings might be “encouraging to those with similarly messy lives.”

I read “What I Worked On” at an opportune time, and musing about messy lives was indeed my main reaction when I came to Graham’s last paragraph. When I stumbled on the piece, I’d just become unemployed for the first time in a decade, after my very first layoff. And as I’ve gone through countless interviews to find my next job, I’ve had to repeatedly give the spiel of my career—starting all the way back with college, as I’m often explicitly instructed. In these loops, I’ve found myself having to deliver my own capsule-sized “What I Worked On”—but rather than a distinguished computer scientist’s retrospective of a life that has come into beautiful focus, it is instead a Small-Time Data Scientist’s Edition at mid-career. The challenge of the latter type is calculating the trajectory in mid-flight—fitting a curve to noisy data—and needing to present something to a prospective employer who wants to hear your grand plan, that parsimonious model that governs the whys of your path. Time gaps beg for explanation; sudden shifts in role require motivation; a theme has to be extracted (or ex post invented) by you because narrative coherence implies a kind of thoughtfulness in your professional dealings. It’s the antithesis of Paul Graham’s lesson: if Graham wanted to demonstrate by his own extraordinary example that messy lives can indeed work, I’ve often felt the pressure to elevator-pitch a completely logical life in order to convince employers of my proper functioning.

Following Graham’s model, I sat down and wrote out my circuitous professional life as a data scientist in detail, starting with school and running through my academic jobs and the five VC-backed startups I’ve worked for. I had several goals for recording my own version of “What I Worked On,” and the top one was simply to work through my own messiness and see if I could not discover some patterns. This is a very detailed account of projects, so the intended audience is definitely other data scientists or people who work in the tech industry. Beyond this self-examination, though, I also thought it could be interesting to document what a data scientist’s career looks like for someone who went to college before “data science” was a mainstream term—and who thus depended on the investment and bets of others to learn on the job. Finally, I did want to try extrapolating that trajectory to figure out where I might be landing. For what is applied statistics if not using past data in some manner to gaze into the future?

Contents

- College (2004–2007)

- Kellogg and Chicago Booth (2007–2009)

- Groupon (2010–2013)

- Bonobos (2013–2015)

- FiftyThree (2015–2017)

- Care/of (2017–2020)

- Maven Clinic (2020–2021)

- 2021

1. College (2004–2007)

I took microeconomics in my last year of high school. I fell in love with its concepts: utility, opportunity cost, decisions on the margin, equilibria on easy-to-understand graphs. I started college thinking that I wanted to become a high school English teacher because I loved teaching, writing, and literature. But I eventually got swept away by my economics fascination and by the popularity of the intro course to the economics major at Harvard (Ec 10 had the highest enrollment at the university). This was also at the tail end of an era, before the Great Recession, when investment banking was still the goal of many ambitious undergrads optimizing for a payday—and right before interest in computer science surged with the rise of tech companies like Facebook.

In my head, English teacher instantly pivoted to economics professor. But when I started college, I had no idea that the Ph.D. required to become a professor was a research degree. Where I came from, I always felt pressure to earn the highest degree, just because. So in preparation for winning that stamp of approval, I got jobs as a research assistant and a teaching assistant, because that’s how you got into a doctoral program. I did odd jobs for a game theory professor named Attila Ambrus, and I TA’d calculus and linear algebra. With my literature days far behind me, I went fairly deep into fields that I didn’t have a natural talent for. I’ve always been a better writer than a quant, but prestige-chasing was a strong force in my life at the time, and it drove me to try competing on territory quite foreign to me.

I was a student with no “social capital”1 for knowing how to behave in and take advantage of a top research university. When I look back, I’m often sad about how much opportunity I squandered, because I’d won a coveted golden ticket whose worth I could barely exploit. (I was also dealing with debilitating social anxiety that peaked in college and didn’t start to improve until I was almost 30—a whole different topic that I’ve written about before.) I often did things that fit other people’s definitions of success instead of exploring my true interests and strengths. But while the choices to switch from English to economics and to pursue a research career weren’t very well motivated, the path I ended up choosing set me up nicely for the rest of my career, and gave me some wonderful experiences in spite of that mentality to follow the crowd or please other people.

My research assistantship with Attila, the game theorist, allowed me to cross paths with one of his collaborators, Parag Pathak (now a professor of economics at MIT). Parag was a graduate student and co-author of Alvin Roth, a prolific scholar at Harvard Business School who blazed trails in experimental economics and market design. On Parag’s recommendation, I took the graduate class on experimental economics taught by Al Roth, who ended up becoming the adviser of my senior thesis.

Through that class and my thesis, I got great exposure to the behavioral side of economics. I loved learning about equilibrium concepts from game theory and their inevitable conflict with empirical results from real people in a lab setting.2 I also learned how to write a research paper from beginning to end—not just the literature review and the statistical analysis, but also grant writing (I needed money to pay the participants in my trials) and IRB applications to experiment on human subjects.

Al Roth would eventually win the economics Nobel a few years later for his work on market design. While I’m filled with so many conflicting feelings about Harvard because of how poorly I fit in, I’ll always look back on my work with Al as a testament to how magical the place can really be—how a student so confused and unpolished could still randomly stumble into extraordinary experiences in spite of himself. (Imagine what it’s like for the well heeled and well prepared!)

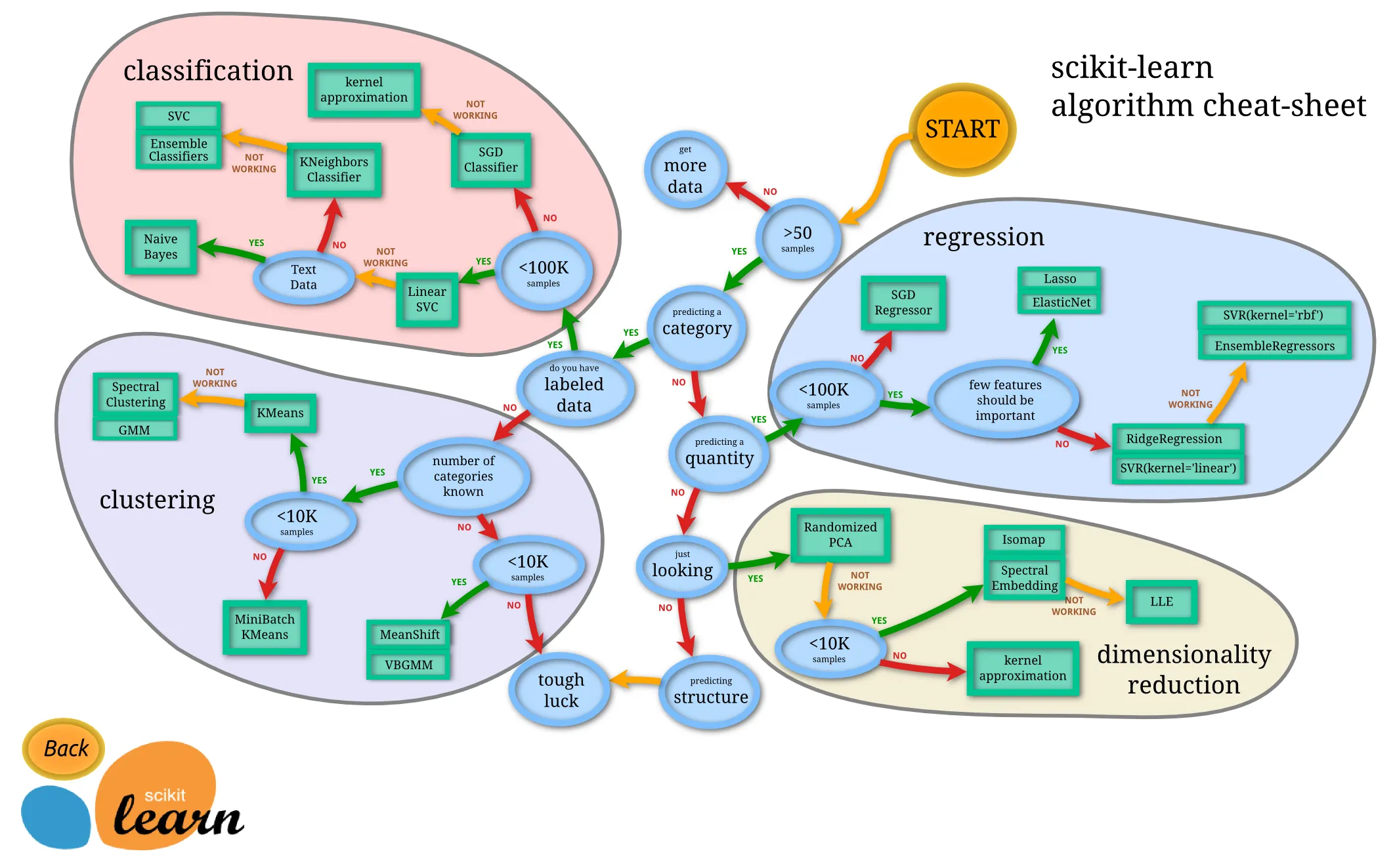

Later on, I discovered that an economics degree is actually excellent preparation for a career in data science. I might even claim it’s an underrated option. Like physics, economics trains you so well on the interplay between the theoretical and the empirical: one day you’re writing a model that’s pure theory (dynamic programming, stochastic processes, differential calculus), and on another you’re going deep into data cleaning and regression analysis. Moreover, the discipline of working with the generalized linear model and its assumptions is so different from throwing things into scikit-learn—but that background in classical statistics is an essential foundation to have when encountering novel problems in the wild, and when explainable models and causal reasoning are still important to your applications.

2. Kellogg and Chicago Booth (2007–2009)

After college, my partner started a graduate program at the University of Chicago. Fortunately, because of the close relationship between the economics departments of the University of Chicago and Harvard, it was easy to find my first full-time job in our new city through my professors’ networks. I found a research group split between the business schools of Northwestern (Kellogg) and U of C (Booth). I worked for two finance professors who were very interested in the kind of experimental economics that I’d done with Al Roth, as well as the research area of culture and economics.

In my first year at Kellogg, I started putting my stats and rudimentary programming into practice. I had used proprietary software like Stata, Mathematica, and MATLAB in school assignments, and the first time I used MATLAB at work was to simulate a probabilistic model on the transmission of culture across generations. Since that paper, I’ve always loved the idea of using simulation to play with analytically intractable models; I just rarely get to do it in practice. (I tried to do a simulation for an assembly line years later at Care/of.)

On the experimental side, my professors were interested in assembling a large dataset that tried to predict the future career success of MBA students (as measured by something like salary) based on a number of covariates measured while they were in school. Some of the predictor variables were obvious controls—like GPA and GMAT score—while other ideas were more exotic and delved into psychology, like measures of psychological resilience or performance in trust games from game theory. When I look back on this time, I’m amazed by how we handled data management before version control and cloud storage. The data files were Stata .dta files; the cleaning scripts were Stata .do files. These often lived on local computers, or maybe on an intranet that wasn’t easy to collaborate on. Knowing what I know now about modern software engineering and data warehousing, I can deeply appreciate the innovations that GitHub and AWS brought to the world.

I left this research group after two years because I started getting the nagging feeling that I’d left behind an artistic calling when I abandoned English in college. I quit with the intention of becoming a filmmaker (maybe an analogue to Paul Graham’s painting?). That’s its own story, which I won’t cover here. But after a year of floundering on that detour, I landed in the startup world, where I’ve now been for more than ten years.

3. Groupon (2010–2013)

I held three different positions at Groupon: operations and data manager of the editorial department, business intelligence analyst, and (briefly) product manager. It was an extremely hectic place, but I learned a lot: I joined a year before the IPO and went through the hypergrowth and the whole process of going public and the aftermath. Groupon was also the beginning of my transition from classical statistics to what we now call data science.

In editorial, I was responsible for the data of a 400-person department. We were fully separate from Groupon’s proper data teams, so I ended up building a very primitive ETL process with two data analysts I hired. At the time, I knew one scripting language, Perl, and I had no idea how to write software. So our proto-ETL ending up being Stata .do files—you use what you know!—which were kicked off manually by my analysts instead of by any kind of scheduled job. Funny (or horrifying) to think about this now—but from a pedagogical perspective, it can often be an invaluable learning experience to build something with zero priors on best practices. You actually end up designing some known structures from scratch, out of necessity—and for the things that you didn’t architect properly, you’ll never forget that mental link between your naïve implementations and the standard methods you learned afterward.

I became a BI analyst because of a man named Dave Glueck, Groupon’s director of BI who had previously come from Netflix and who was very well versed in how to architect a data warehouse properly. Dave is one of only two people in my life who took a bet on me to start a role I had no prior experience in, and who bet that I had the raw skills to rapidly learn on the job. I had zero exposure to databases and SQL—the core things you have to know as a BI analyst—but Dave sponsored my transfer out of editorial anyway.

I remember buying the O’Reilly book Learning SQL and reading it on my first days in the new role. (Stack Overflow googling as the bulk of your day was not yet a thing, and high-quality tech blogs and tutorials were not yet ubiquitous.) As a BI analyst, I learned that a scheduled data pipeline could be kicked off by a server every day; that SQL is time-tested, robust, and deceptively simple; that relational data warehouses could be organized as immutable “facts” with “dimensions” stemming from them like spokes on a wheel. And I learned how a web-based analytics tool could act as a user interface on top of that fact-dimension data model.

My time at Groupon ended because of the toxic management they had in that era. Amazon executives were hired to be the adults in the room and made our department’s sole mission to output a gigantic “weekly business review” that was just an unimaginative vomiting of reports. When our speed wasn’t fast enough to their liking, one of the executives took all the data engineers and BI analysts into one room—with our Palo Alto team members also on a videoconference—and launched an hour-long, interstate, expletive-filled rant about our poor performance. I was about 27 years old at the time, and I was shocked to see such a nonsensical and vile display, and to watch everyone taking it in silence. (It is not a scene that would ever transpire in the age of live streaming via smartphones.) I vowed to myself never to be so desperate for a job that I would ever have to be debased this way again.

Dave left the company soon after this incident and eventually landed at the clothing company Bonobos as their Sr. Director of Data Science and Engineering. A change in my own role to a data product manager wasn’t enough to keep me, and as soon as Dave could make his first hire, I followed him to New York to join Bonobos.

4. Bonobos (2013–2015)

Dave Glueck plucked me out of Groupon editorial, and he also gave me my first data science title. It was again a job that I had no direct experience in, so I once again marvel at his generosity and trust in me to learn an entire discipline on the job. As I mentioned earlier, the kind of math that you see in an undergraduate economics program is a great start to a data science education. But modern data science quickly departs from linear models, and I had a long way to go before I could credibly call myself a data scientist.

Dave and I ended up learning parts of the scientific Python suite alongside each other. Numpy and pandas were well on their way to becoming the crystal-clear standard for all this work, but it wasn’t quite the age of the Anaconda distribution just yet. 2013 was the year I learned about supervised learning, random forests, support vector machines, recommender systems—things that you would see in a standard data science program today. A lot of my work at Bonobos was building ETL pipelines more formally than I had at Groupon. In fact, this has become a common theme in my career of startups, as young companies always need data engineering and analytics before machine learning. These are the immediate, pressing needs. So if you are a data scientist in title, but the data engineering and analytics aren’t properly set up, you will invariably be doing data engineering and analytics.

There are three big projects that made a lasting impression on me at Bonobos, and they were all related to marketing. All credit goes to Bonobos’ marketing VP, Craig Elbert, with whom I later reunited at Care/of and who became the closest thing I’ve ever had to a mentor. Craig was by far our department’s strongest ally, always curious about what we were doing and how we could all work together.

(A) On the ETL side, I learned about digital advertising and marketing attribution. Bonobos launched at a time when advertising a new brand on Facebook was relatively easy and cheap. The economics for a direct-to-consumer business were quite favorable in the first several years of Facebook Ads. This is a huge topic, as the parameters have definitely shifted in the intervening decade. But any break-even analysis of new customer marketing will have cost to acquire the customer on one side (e.g., what you paid a channel like Facebook), and some version of lifetime value on the other. The latter could be lifetime contribution margin dollars, for example, as a stricter bar for profitability.

So let’s say you are a marketer trying to allocate your budget B dollars across a set of candidate channels {1, … , n}. Other channels include things like Instagram influencers, podcasts, and direct mail. Let b_i be how much money you put into channel i, constrained by the total sum over all channels being at most B. You need to reason through whether a channel i is profitable or not, and ultimately whether your chosen overall allocation b = (b_1, … , b_n) is the payback-maximizing one, b*, over the feasible space. A complex data pipeline must exist for you to be able to say that a new customer even came from i (or partially came from i, in more sophisticated models!). These concepts were completely new to me, but they are core to building a profitable digital business today. I’m glad I got my first exposure to them at Bonobos.

(B) At one point, the marketing team asked how we could analyze the effectiveness of podcast advertising in different geographical areas if we didn’t have any instrumentation for attribution (e.g., a promo code to link a podcast listener to a purchase). This problem led me back to difference-in-differences regressions,3 a common tool for econometricians to attempt causal reasoning when there is a credible comparison group to serve as a counterfactual cell. It was nice to be able to pull from the economics foundations at a time when I was often trying to catch up on newer concepts.

(C) Finally, my biggest project at Bonobos was getting a kind of recommender system off the ground. The only recommender system I’d encountered in my reading up to that point was item-to-item collaborative filtering, but it was perfect for a clothing company where a “user × item” matrix was a very natural structure. Bonobos relied heavily on sending multiple marketing emails per week, and it is reasonable to assume that a typical customer doesn’t want to see every single mailer. So if the marketing team wanted to advertise blazers on a Tuesday, then the data science team tried to narrow down the subset of the large mailing list that should see that mailer, guided by cosine similarity scores between the target blazer and the items a customer already owned.

We ran several experiments pitting human curation against this recommender scheme. Using “revenue per delivered email” as the success metric, we could easily achieve 1.5x improvements over the status-quo baseline. In the most extreme case, we even achieved a 4x improvement. When I left the company, there was still a long way to go to productionize this model as a working system. But it was the first time I felt that the new data science concepts I’d been learning were paying off in concrete ways, with a large potential impact on revenue.

I moved to New York when the city’s tech scene still felt like it was in its infancy. Bonobos and Warby Parker were often spoken of in the same breath, as pioneers of direct-to-consumer brands that were “digitally native”4 but also omni-channel with their physical presence. Looking back, I feel fortunate to have been close to the root of a great family tree of NYC tech. I think of this company and that time quite fondly because it spawned several entrepreneurial ventures in consumer products, including one that I later joined in 2017 and that became the best job I’ve ever had.

5. FiftyThree (2015–2017)

My next gig was the first time I was in charge of all the data, the first time I became aware of good software engineering practices, and the first time I dipped my toes into deep learning.

FiftyThree was a software company that created the sketching app Paper and the presentation app Paste. I was hired as the Head of Data Science and got to design the data stack for the first time. As I was leaving Bonobos, my data engineering colleague there had just begun playing with Spotify’s Luigi for ETL orchestration—a move away from proprietary software for that component of the stack—and I ended up using Luigi for ETL5 and Amazon Redshift for the data warehouse. Because none of the data practice existed at FiftyThree yet, I once again poured a lot of effort into data engineering and analytics, with the hope that data science work would emerge in due time.

The dev ops engineers at FiftyThree taught me invaluable lessons on good software engineering. I vividly remember passing my first data pipeline to one of the engineers, Matt Cox, so that we could get it running on a normal schedule. Matt completely tore it apart and revised it, thus beginning my education on how real engineers code. There’s a long list of tiny things he showed me that I’d just never seen before as a self-taught person in this field: Docker, managing package requirements, managing secret keys, shell scripting, gitignores and READMEs, linting, the AWS CLI, true object-oriented programming in Python. I really leveled up here because someone was willing to teach me the things I didn’t know. This process can be embarrassing because it feels like your impostor status is on full display, but it is necessary for growth. And when I coach people who are in the same situation as I was—with math and stats from college, but barely any real-world programming experience—it’s easy for me to approach them with firsthand understanding.

On the ML side, the breakthrough project for me was when FiftyThree’s design team asked if we could do image classification on assets that a user uploaded to the Paste app. They wanted to know whether I could classify images into chart, sketch, natural image, and other categories, so that Paste might further process the asset based on the classification. Problems like “Is this a chart?” (hot dog/not hot dog) got me into computer vision for the first time, and I studied both the traditional computer vision that you get from OpenCV as well as deep learning. TensorFlow launched in my first year at FiftyThree, and I developed some pretty good intuition for how convolutional neural networks “see.” I also saw how I could use a pre-trained model like Inception v3 for transfer learning. Deploying TensorFlow was a much bigger challenge in those early days—I couldn’t figure it out by myself—and as the term “MLOps” becomes more mainstream, I can appreciate just how difficult it is to truly productionize an ML system end to end. (The Berkeley course Full Stack Deep Learning has made great strides in codifying this knowledge.)

Obviously, deep learning has revolutionized an entire industry, and on a personal level, it reinvigorated my interest in research. For the first time since my academic jobs, I could see myself going back to school and studying a topic like this deeply. I discovered new problems—difficult, important, intellectually exciting—that I knew I wanted to be a part of.

6. Care/of (2017–2020)

Craig Elbert, the marketing VP at Bonobos who was behind the most exciting work I got to do there, co-founded his own direct-to-consumer company for vitamins and supplements in 2015. He recruited me to start the data team, and I joined right as the Series A was finalizing in 2017.

I’ve written about Craig’s impact on my life several times, in LinkedIn posts and internal Care/of messages.6 It’s hard to do justice to the topic here; the theme of mentorship really requires its own treatment. But from the beginning, Craig had been going out of his way to champion my work when we were just acquaintances at Bonobos. And even after I’d left for FiftyThree, he was still trying to find ways to connect me to new people and to keep in touch. He is a rare leader who can juggle startup financing, the aesthetics of brand marketing, curiosity in high tech and data, and sincere empathy in management. I’ve admired the way he can switch between sober-business-presentation mode and class-clown mode, but sometimes not know when; the way he handles crises with a cool head; the way he writes. And with Care/of, Craig gave me my biggest canvas to execute an ambitious data science program, as well as the space to be my weird self without reservation.

Health tracking

The core business problem that Craig planted in my head when I started at Care/of was how to convince skeptics that supplements are even doing anything. If day-to-day changes after taking supplements are imperceptible, how can we bridge that knowledge gap and convince the unconverted that daily supplement intake is actually beneficial? I became somewhat obsessed with the idea of health tracking over the next few years, usually in the context of wearable devices like the Apple Watch or WHOOP,7 but also through the manual logging of events via an app. If we wanted to rigorously show, for example, that turmeric reduces inflammation, or that rhodiola increases alertness,8 we needed to collect both feature and target data, and then create models that controlled for both user attributes and environmental factors.

With Craig’s help, I composed a sort of vision statement to express these high-level goals. It was ambitious and arguably too far afield for a company whose flagship creation was a physical product. In my ideal world, we could have tested out these digital ideas and possibly attracted the attention of investors or buyers in health monitoring. Two of my data scientists learned how to make their own iOS apps and prototyped various ways that we could collect the necessary datasets for health outcomes. But in the end, after a year or two of dreaming, this product vision didn’t match what the majority of our investors and executive team were interested in.

I don’t regret pursuing a grand vision for ML applications at the company, but I did learn a lot about this kind of high-level strategic alignment across investors, senior leaders, and the rest of the organization. It’s hard to execute on a years-long plan, as you’re so often operating week to week, quarter to quarter, with surprises throwing you off course even at that modest cadence of short-term planning. Keeping a large company aligned on a years-long strategy is truly a skill that takes years of operating experience.

In addition to this big-picture work on health tracking, two more areas at Care/of were crucial to my professional development: computer vision and people management.

Computer vision at the fulfillment center

Our computer vision model for pill counting harks back to my initial experience with CV and MLOps at FiftyThree. The project started when I visited the fulfillment center and shadowed the quality-control stage where associates had to verify the number of pills in sealed daily packs before the overall package could be finalized and shipped. I knew from my work with OpenCV and TensorFlow that this was the perfect setup for some CV automation.

My data scientist who pulled this off, Eric Dougherty, convinced me over time that deep learning was the way to go. I was wary of starting with deep learning because I’d thought a traditional CV model could easily do the trick with far less computation. I’d seen algorithms in OpenCV like the watershed, and deep learning felt like overkill. Eric turned out to be completely right, because the physical conditions between the camera and the target objects were not as idealized as they were in the watershed demos: lighting conditions were variable, a translucent film obscured the pills, and the pills themselves could also overlap in the depth dimension. The easiest way to capture all this natural variation was deep learning, not painstaking, brittle feature engineering with traditional CV.

Eric framed the problem as object recognition and found a solution in Faster R-CNN. In addition to the normal image classification from CNNs, Faster R-CNN also has a “region proposal” step since there can be an arbitrary number of the target object to detect in an image. It was a brilliant choice to apply modern methods to the task at hand.

The process to get a trained model all the way to deployment had many phases. Bounding-box labeling with Mechanical Turk had its own cycles, since we had to deal with low-quality annotations from Turkers in various ways, from averaging multiple raters for the same image, to drawing the boxes ourselves. There was physical hardware involved to get cameras mounted in the existing machines. And getting the approval of our quality department required an accuracy threshold and a checking process that could pass muster with the FDA.

Overall, the CV project was an excellent, end-to-end demonstration of the complicated process to get deep learning into production. For its sophisticated model and its role in cost-saving automation, it is the most concrete contribution of modern data science to a company that I have overseen.

People management

“What’s your management style?” is a basic question that often trips me up. I could use an hour interview to talk about my approach to people management. So when I get the question in interviews with the expectation that I’m supposed to give a 2- or 3-minute answer, I get sad that a multidimensional skill is essentially reduced to “How big have your teams been,” “Have you managed managers,” “Have you fired underperformers,” and “Do you do agile sprints?” When I detect that interviewers conceive of people management this way, I know that they do not value it as a specialized skill that is honed over time.

I care about people management as much as I care about technical work. At a young startup whose culture is just getting established, I took it as a responsibility to foster a work environment that people wanted to come to every day, and to create jobs that did more than just pay the bills. I expect the same thing out of my own job, so when I have the privilege of being in charge, I make sure to build a work culture that I would want myself.

If I had to distill my “style” down to principles, these are the main ones that come to mind:

- Promoting continuing education. Keeping up with the latest research in your field is important, and there are many ways to do this: discussing papers in the news, going to informal meetups, paying for professional conferences, giving lunch & learns.

- Prioritizing discussions about career path. “What do you want to grow into, and are you regularly doing things today that build toward that?” This is a conversation that should be happening very frequently in your one-on-ones.

- Home life is always more important than work. Home wins all the time. Flexible work arrangements are finally becoming more mainstream, but this has been a requirement of mine for a long time. It’s the only sensible way to think about work in an advanced society.

- Vulnerability and humility. Admit when you don’t know something, when you’ve made a mistake, when you’re frustrated. If something at work or in the world is out of balance, find healthy ways to discuss these issues.

- Write often. Write up preliminary data science results as they come in. Write up strategic thoughts. Write up anniversary celebrations. Write up failures. Everyone knows “communication” is important, but many people shy away from one of the best tools that the human mind has for synthesizing information.

- Always take the time to praise good work, especially as you move up the ladder. Jobs are hard, and sometimes just knowing that the value of your work is genuinely understood by someone in charge is enough to keep you going. When making positive feedback public, it should be specific (No “She’s such a rock star! She absolutely killed it!”). You should outline the work’s importance to the wider team, as it can often be subtle, especially for back-end work or data science.

I was able to work out a lot of these principles because Craig trusted me to hire my own team and let me try out unorthodox things. They’re not without caveats: too much vulnerability could sacrifice a show of strength; too much writing could be bothersome noise to people unwilling to read. In general, this style requires a significant emotional investment, which burned and exhausted me sometimes. But as I mentioned, this is a skill just as much as computer vision is a skill, and it deserves equal space and consideration in an examination of professional development.

7. Maven Clinic (2020–2021)

I was only at Maven Clinic for eight months. It was my first time working with data on hard medical outcomes: predicting C-sections and NICU admissions at the patient level, as binary classification. I was excited about the opportunity to fuse ML, classical stats, and the domain knowledge that the medical doctors on staff could bring. The story is complicated, but what I wanted to do ended up not aligning with where the company was, and I was effectively laid off amid the COVID pandemic.

8. thank u, next (2021– )

As I’ve been interviewing this year, I’ve found myself on a kind of plateau. In some ways, I feel well qualified to be the VP of data at companies similar to the ones I’ve already worked for. In other ways, my lack of seniority is apparent to me when certain gaps in my self-taught knowledge emerge: I’ve never worked with data big enough to require Spark or Scala; I haven’t worked with deep learning enough to have internalized all the little tricks of the trade, the folk knowledge for what to try when your model isn’t working; I don’t know enough about microservices, caching, or sharding to pass a systems-design interview. Overall, I’ve always felt quite broad and not deep. This type of profile is often most attractive to early startups that want you to cover many roles and that value zero-to-one soft skills—and is not desirable at companies that have a very specific definition of what a qualified tech worker looks like.

Epiphanies pepper Paul Graham’s “What I Worked On,” and now at this juncture, I’ve been musing about what my own big career lessons are. (Graham asserts, for example, that chasing things that lack prestige is often a good sign that your motivations are in the right place.) In the face of numerous rejections, including some from companies I was really invested in and felt a strong connection to, I’ve struggled with the specter of the question, “Am I actually the problem?” As you gather more and more rejection data, it’s hard to maintain the null hypothesis that it’s not you.

Sitting with that self-doubt, I’ve started training intensively on technical skills again. I’m following along with courses like Full Stack Deep Learning. I’m studying for engineering interviews like algorithms and systems design since I often run into them in some form. I’ve been deeply exploring the nonprofit OpenMined, which makes privacy-preserving ML software. I’m taking their courses and attending tutorials with the intention of becoming an open-source contributor. I also think I’m finally getting to a point where I could start my own thing, and actually be good at it. If I boldly claim that my breadth is worth something, I should probably just take that bet myself.

These are all tactical next steps, looking forward—but the retrospective lesson still remains. Finishing this post and feeling profound gratitude for the trust that people placed in me, I have wandered and returned to some sparkling wisdom from the film Ratatouille, that great work on creative endeavors and unlikely origins. The last time I watched Ratatouille, I was so touched by this statement, in emotional recognition of its uncommon empathy and its plea for the unseen and unconnected:

The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations. The new needs friends.

When I look back at a career of autodidactic groping in the dark, I’m most humbled and moved by Dave’s investment, and Craig’s investment. They elevated me at times when I was truly green, with very little proof of what I could do. And I can only write a long piece like this, narrating vanished projects that only held relevance for a brief instant, trying to reclaim their role and value in my life—trying to turn an interview spiel back into the full career of which it’s a low-dimensional projection, where teams and models and systems were built from scratch and lovingly assembled—I can only record such a history because of the rare patrons who extended their friendship to new creations. There’s no formula for finding these benefactors, so I can only operate by trying to be that patron myself. You may not always have the financial power to hire, but you always have the power to teach. I might have left the English teacher behind, but the teacher has always been there.

-

Anthony Abraham Jack’s book The Privileged Poor (Harvard University Press, 2019) was an eye-opening resource for me here. ↩︎

-

The public goods game and the ultimatum game are illustrative of this conflict, and I often use them as reference points in various kinds of conversation. ↩︎

-

I have heard that Bayesian structural time series are a major generalization of DID regressions, but I’ve never been able to try them myself! https://research.google/pubs/pub41854/ ↩︎

-

For more on this topic, check out Andy Dunn’s initial write-up of this concept in 2016, as well as Nate Poulin’s thoughts on his Digitally Native Twitter. ↩︎

-

Luigi has since been overtaken in popularity by Airbnb’s full-featured Airflow, which I used in Care/of’s data stack. ↩︎

-

This is an indulgent piece and was my internal farewell post at Care/of, but “Episode 1” is my best elaboration on the kind of care that Craig has demonstrated since our Bonobos days: “Under Lights, We’re All Unsure.” ↩︎

-

WHOOP’s CEO recently gave this interview where he vocalized a sentiment I’ve also felt very strongly: “Health monitoring isn’t going anywhere. It’s one of the most important categories of the next five to 10 years—in terms of how profoundly it’s going to change society. It will so dramatically improve health for humanity. It’s actually underestimated, because the version one of wearables was actually sort of lame.” ↩︎

-

Claims like these are highly regulated by the FDA. I am only stating these hypotheses as illustrations. ↩︎