Tenvey

On my father’s cover band, and a rock ’n’ roll lesson

A lot of my musical education came from my dad, whether I liked it or not. He drove my sister and me to elementary school every morning, first in a two-door Datsun bought around the year of my birth, and later, when my parents’ lives as first-generation immigrants achieved some level of comfort, in a gray Toyota Land Cruiser whose new elevation lent an air of control and importance. The drive was so short that it’s amusing, in terms of duration if not of fuel efficiency, to think about it from the perspective of a (now) New Yorker: if a half-hour subway commute, door to door, is acceptable by metropolitan standards, the car in Texas took you several miles farther in half the time.

During those quarter-hour drives, my dad commandeered the music. And without fail, the selection would be an element from this set:

Help!

Abbey Road

Past Masters, Volume Two

The White Album

(very occasionally) Rubber Soul

As these five works were the universe of my music, I might wrongly assume it’s common knowledge that each and every one is an album by the Beatles. To be fair, there must have been an exciting novelty at the time, as the Beatles had not been out on Compact Disc for that long. (The “Wanna feel old?” memes, even the ironic ones, stop being jocular elbows to the ribs past a certain point.) Maybe CD players in cars were fairly young, too. The Datsun didn’t have one; its radio-tuning knob moved a physical display needle—it may as well have been searching for the hiss and pop of a fireside chat. We never dealt with the whole “CD changer in the trunk” ordeal, either, so the jewel cases sat in the interior of the middle console, spine titles facing upward, active album nestled in the nook of the hinged lid above.

We always started a CD from the beginning, so if an average Beatles song is, say, three minutes long, we very consistently made it through five or six tracks before reaching Windsor Park Elementary. For this reason, I knew the first side, and only the first side, of Abbey Road intimately—except that my dad always skipped the sixth song, “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” maybe because it is indeed quite heavy, or maybe because its bluesy ache was a glimpse into some adult desperation from which the kids had to be shielded. (I wonder why it eventually became my favorite Abbey Road track?) There was little variance around that mean of a fifteen-minute journey, but in the event that some stochastic traffic added to our mornings together, I might get to hear the first bars of “Here Comes the Sun,” a song whose tinkling George Harrison guitar could make any kid happy. It’s been a long, cold, lonely winter, and they tend to get longer and colder.

My sister started breaking from established customs—a mantle that I, the younger, often took on in later years—by exploring the silky R&B of Hot Z95 (95.5 KZFM, Corpus Christi, Texas) on her Sony Walkman. I eventually got one, too, from a locked plastic case in the Sam’s Club across town, and as my sonic vista widened I latched onto the inescapable hits of the early nineties: “That’s the Way Love Goes” and “Again” by Janet Jackson, “Dreamlover” and “Hero” by Mariah Carey. I truly love these songs, even today. I recently watched Poetic Justice on a film print at Brooklyn’s BAM, and the lovely Janet/Tupac interplay made “Again” that much more poignant to me twenty-two years after hearing it for the first time. Your politics, your music, and your selfhood are all shaped in this manner: some inherited bedrock foundation whose subsequent strata are inevitably sculpted by the rains and sediments of the surrounding environment.

My dad’s musical instruction did not end with the invasion of TLC and Toni Braxton on the airwaves. My parents bought us a Super Nintendo game called the Miracle Piano Teaching System (How dare it encroach upon Super Mario World!), and I learned what I could of the piano through gameplay imitation. As for my dad, he’d taught himself to play the guitar when he was a kid, and although his lack of formal training meant that there was no structured music theory behind his playing, he intuitively understood those I–IV–V chord progressions and the fleet-fingered transpositions that more than adequately toured him around the history of rock ’n’ roll.

But the implied dilettantism belies the startling extent to which he pursued his pastime. This was way more than a hobby: he had a full cover band that met regularly at our house. There was a cherry-red drum set planted in the corner of our dining room, complete with mounted cowbell for songs like the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women,” a representative piece from their setlist. I heard it played so often that it was like a repertory magic trick whose illusion you’d already deciphered twenty performances ago.

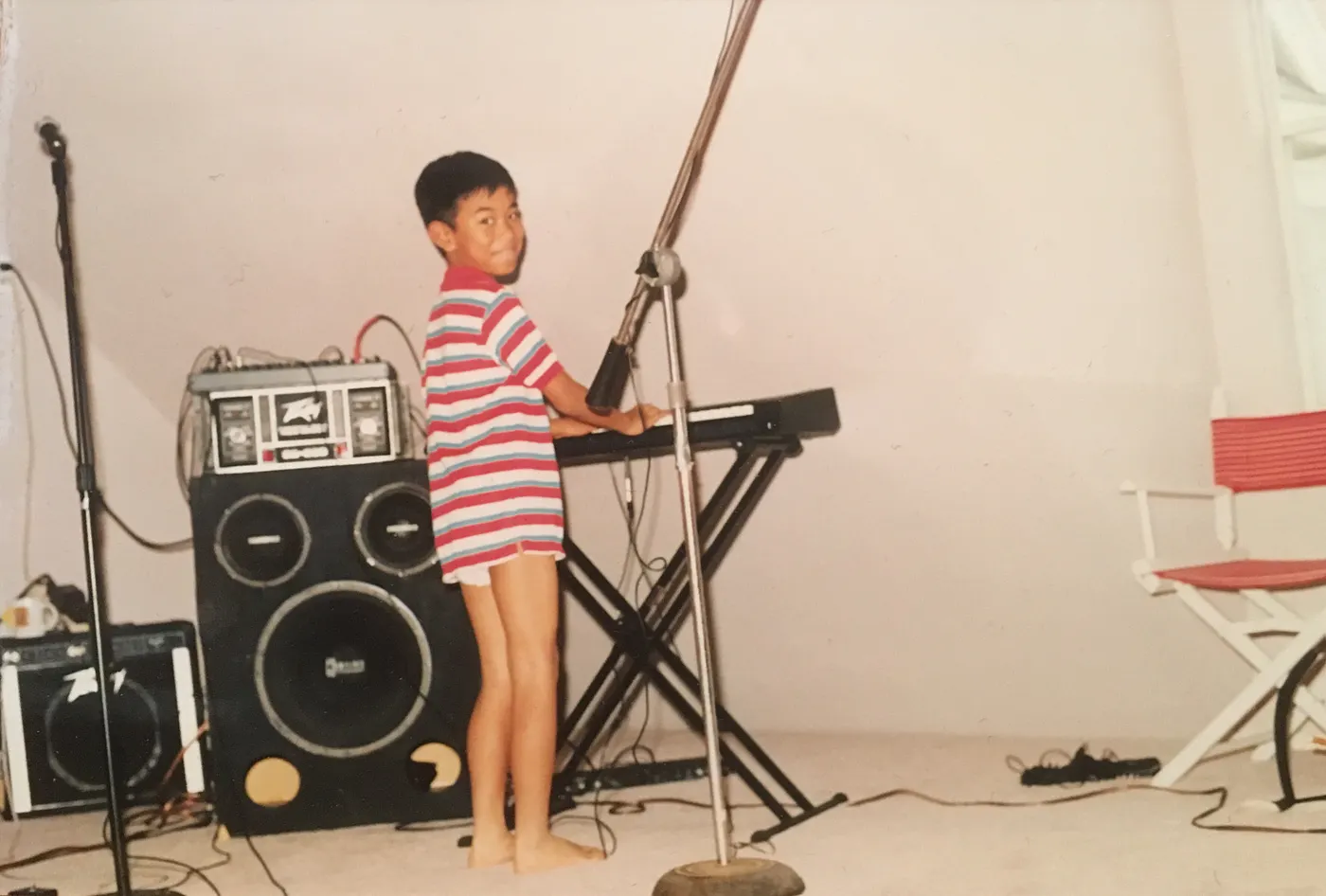

The drum kit was played by a guy named Frank, who proceeded surnamelessly as long as I knew him. Tito Sonny, my dad’s Navy buddy and godfather to my sister, played a shiny black electric bass. A friend of a friend would occasionally pinch-hit to tackle the lead guitar part on “Hotel California.” They all took turns singing, like the Beatles. And if it wasn’t clear from this picture, there were definitely microphones and amplifiers. Sometimes, on family trips to McAllen, Texas, we would visit a music superstore called Hermes (like the messenger, not the scarf purveyor), and my dad would emerge with a Fender Stratocaster or a Takamine acoustic, or a pedal board that allowed for that satisfying, instant pivot from sonorous plucking to grungy power chord.

But the amps, above all, made it legit. My dad’s amps were almost always from Peavey. And for the longest time I thought the brand was actually named Tenvey, because I could not parse the angular typography emphasizing the rocker’s razor edge. It took a different perspective to see the familiar figures take on a new form, though it was a form that had always been there. The Peavey amps were the ones that got the neighbors angry, the ones that shook the walls and broke my mom’s decorative plates, the ones whose sounds were recorded onto cassette tapes for playback, the ones that we hauled upstairs to protect from floods during a hurricane.

My mom dubbed his cover-band rehearsals “tugtog,” both syllables taking a long “ooh” sound—the direct Tagalog translation of “music.” I never learned Tagalog grammar, but I gather that “tugtugin” is something like an infinitive for “to play music.” But her bilingual hybrid could meld parts of speech, and sentences like “There’s tugtog tonight” could just as well be rendered as “Your dad is tugtugging on Saturday”—a sort of Tagalog infinitive comically inflected in the English present progressive.

Their sessions were not just “Hotel California” and “Free Bird.” Though my dad’s tugtugging (now a gerund) was firmly grounded in the sixties and seventies, he unpredictably annexed a particular era of post-grunge alternative, and his band started playing songs like “Comedown” and “Machinehead” by Bush. On his own he would learn “Lightning Crashes” by Live, “Santa Monica” by Everclear, “When I Come Around” by Green Day. In a way it was awkward for me because the kids who bullied me were listening to these songs, too. And as music was the mathematical function that consumed you and spit your coolness level out on the other side, I felt ambivalent when my dad would enlist me to play keyboard parts in genres that didn’t feel like my own.

After the tutelage of Nintendo, I eventually learned some obvious piano parts in Beatles songs: “Let It Be,” “Hey Jude,” the harpsichord-like interlude of “In My Life.” We bought sheet music from Music Mart at the corner of Moore Plaza, and I usually ended up playing from the guitar chords because the piano arrangements invariably followed the vocals like a verbatim transcription. Soon, though, my dad wanted the orchestration of Bush’s “Glycerine” to join his four-chord lament, and we would select the synthesized strings from the Miracle keyboard and figure out the counterpoint violin in its refrain, as well as the ten funereal tones that close out the record. But it just wasn’t something that stuck for me, and I didn’t work on any music creation past adolescence. Your childhood decision making doesn’t carry with it a master plan, or deep motivation, or well-defined consequences; all of that comes later, when adult-you begins to overthink and assign known patterns to the amorphous past. For similarly ambiguous reasons, I have absolutely no recollection of the end of tugtugging. After their countless performances at Christmas parties, rotating through residences and the naval base, I don’t remember the last waltz. There was no farewell tour: perhaps it was put away like childish things, or perhaps it dissipated promptly like a misty, crepuscular reverie upon reality’s sunrise.

T he first time I heard the Rolling Stones’ actual record of “Honky Tonk Women,” I was driving somewhere on the Kennedy Expressway in my girlfriend’s car in Chicago. By this time I was in my mid-twenties, and the clanging cowbell on the radio recalled Frank Blank’s assured beat from years and cities past.

Except that it was an utterly different song. Stale magic trick it was not—this was actually a damn good record! This ain’t your father’s “Honky Tonk Women”! It’s possible I didn’t even know it was a Rolling Stones creation till that moment. Keith’s swaying, swiveling guitar, constantly licking upward like a flame; the saxophonists’ reeded sound alternately plunging, hopping, alighting; Mick’s inimitable swagger—it’s an unenviable task to mimic these performances, and I don’t fault the cover band for not quite attaining that magic, for how could they? (I also learned that my dad had censored the line “I laid a divorcée in New York City” so that, rather than laying her, he merely met her, maintaining a palatable anaphora with the gin-soaked barroom queen of the previous stanza.) But it was a revelation, a new understanding of his love of rock, and of the rock ’n’ roll that indisputably made it into my veins.

These rediscoveries happen often: I make it to side two of Abbey Road and experience its seamless segues, its reprise of themes; I revisit songs that passed over my youthful head—“Yer Blues” and “I Will” on The White Album—and wish they had been in my life just as long as “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” and “Drive My Car” have been. By extension, I then start to wish that music itself had been in my life that long, and realize that I played a principal role in its interruption.

While the great majority of my art consumption is cinema, there is a certain catharsis that is only achieved aurally. It is in the raw, joyous freewheeling of “The Modern Age,” the second track on the 2001 album Is This It by the Strokes, who didn’t give a fuck before not giving a fuck was cool. I hear this record and feel a primitive anarchy that makes me want to expand my limbs in impossible directions and feel the bliss of a life that I’ve never lived but that could and should be mine.

Piano with my dad always had that accursed connotation of “compulsory,” like Abraham Quintanilla making Selena practice in Selena (Corpus hat tip). I didn’t like playing these songs, or songs that I never chose myself, and I didn’t want to be a musician. I was the only person in my Filipino clan who wanted to do visual art when it came time to choose a middle-school elective; everyone else had gone on to concert band. My sister, who started playing the flute in band, felicitously unlocked my dad’s ability to perform Chicago’s “Colour My World” as a trio: I transcribed the piano and flute onto blank sheet music, and we played the whole thing from the opening arpeggio to the slow trill concluding the flute’s solo. As I didn’t continue with any music practice or instruction after fifth grade, ignorant of how these pedagogic decisions can compound into the future, I ended up shunning a formal music education for a random confluence of reasons. Maybe it was the bullies with their Marilyn Manson and Korn, surprised that I knew Bush’s albums; maybe it was because I preferred to learn the piano parts of “Again” and “Hero” instead of the rudimentary Music Mart curricula, but didn’t even know that was ever an option. And I never second-guessed the decision because I soon got swept up by the absolute insanity of looking good to an elite college, a multi-year gambit that I regret with each passing year. So maybe it was because I didn’t want to conform to the Asian parent’s dream of turning into someone like the musician Lang Lang, or a metaphorical Lang Lang, as it were, playing a magisterial grand piano in a hallowed concert hall: I often see the Chinese dad at the Herald Square subway station turning his child into a busker, watching imperiously as the kid perfunctorily bangs out the Love Story theme to some tinny recorded accompaniment, or the famous rondo from Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11; and I think to myself, like anyone who is fiercely independent, or who is bruised by childhood taunting, that I really did crave a life on my own terms, where I got to choose from life’s infinite menu and where I actually had fun. But now, deep into adulthood, I can think of few leisure activities that would be more gratifying than knowing how to play the guitar solos of the Strokes and blasting them deafeningly on a Tenvey amplifier.